Movement

If the actor is an artist … his creation is himself, both as subject and as object, beginning and end, matter and instrument. Therein lies the mystery: that a human being can think of himself and treat himself as artistic matter, play on himself like an instrument with which he must identify while never ceasing to be distinct from it, simultaneously active as a person and impersonating that activity. – Jacques Copeau, Texts on Theatre (1929)

Actors create life on the stage by embodying characters that have particular rhythms, weights, levels of energy, and turns of phrase. Whatever approach actors bring to their job, they are conscious that with each moment and gesture they are communicating something to the audience.

My study of movement rose out of my needs as a performer and those of the actors and performers I teach and coach. The foundation of my approach is the movement work developed by Trish Arnold. I have developed a focus on Mindbody Perception and Physical Awareness that brings actors into a new relationship to and presence with their bodies in space. With my students I also explore expressive movement in the contexts of physical character work, actor-audience relationships, character analysis and creating emotion from sensation.

As a performer and teacher I am committed to bringing truth to large physical expression – through internal, imagination exercises and external, physical-shape exercises. The physical language of acting is not only naturalistic; the inhabiting of stylized and exaggerated physical states is vital to much of the world’s theatre. Even the poetic world of Shakespeare cannot live fully in an actor’s body that is exclusively contemporary or strictly naturalistic in its energy. Actors benefit from experimenting with forms of play that move beyond naturalism, increasing their ease in expressing themselves truthfully in a variety of styles.

Recent findings in neuroscience confirm that humans are all experts at reading the nuances of human behavior. We have evolved to register and evaluate in an instant, for example, information about a person walking towards us on the street, picking up physical cues about whether we are facing friend or foe, what the other’s intentions may be, and many other details. And we bring this expertise to the theatre as members of an audience: we are neurologically primed to make sense of what is happening on the stage. We look for clues to each character, why this one is doing what he is doing and what his relationships to the other characters are. To every subtle gesture, every turn of the head or vocal inflection of each actor on the stage – sometimes consciously, sometimes not – we assign meaning.

Fundamentally, the actor must have a command of her instrument, her mindbody, just as musicians must have command of their instruments. Dancers also use their bodies as instruments, but they employ a prescribed physical vocabulary. Actors have no such vocabulary. There are givens, to be sure – text, circumstance, blocking, costume – but what is important is how the actor transforms those givens into a live character on the stage.

For the actor, to have command of her bodymind means to be able to release and shape the body’s energy, to fill the space, and to have her imagination, intellect, emotions, and psyche reflected through her body so that she may express the subtlest and the broadest of impulses. In order to reveal fully the character to the audience, the actor’s habitual physical patterns must become conscious to her and available to her modification and adaptation. This involves utilizing the body in several complex ways in order to inhabit the character with the implications of personality, time period, class, cultural, and gender manifestations, style of the play and how interacts in a live arena with the audience.

Movement: Trish Arnold

Basic movement work should not be confused with fitness practices, physical re-training techniques, or dance forms, all of which are wonderful skills to have; none, however, directly addresses the specific physical needs of the actor’s instrument.

I began to teach after studying Trish Arnold’s movement work in London and then apprenticing with her in the early 1970’s. This basic movement work develops a sense of impulse and connection to breath, and directly enlivens the actor’s imagination and physical expression. I have taught this work to actors in theatre companies, university drama schools, independent workshops, and for Linklater voice teachers. I also use it in my own practice as a performer. It is not intended to be performed per se but rather to support the actor.

At the center of Trish Arnold’s work is the Swing. There is a release down towards gravity, and then the impetus of rebound upwards, followed by a delicious and powerful moment of suspension at the top, before the whole impulse to swing begins again. So there is both a down and an up impulse to be experienced, in a “rhythmic vitality,” as Jane Winearls calls it.

The rhythm of a Swing may be compared to the journey of a wave breaking on the shore. There is the break of the wave with its forward propulsion, which continues onto the sand, diminishing with the last bits of foam, then a moment where nothing seems to happen, and finally the fast pulling out of the water. That suspension between the inward and the outward flow is critically important. We notice a similar pattern in our breathing: there is an inhalation and an exhalation, and between them a liminal moment of suspension. (To offer a contrast, a metronome or a pendulum also exhibits a steady alternation, but without impetus or recovery.)

The rhythm of a Swing may be compared to the journey of a wave breaking on the shore. There is the break of the wave with its forward propulsion, which continues onto the sand, diminishing with the last bits of foam, then a moment where nothing seems to happen, and finally the fast pulling out of the water. That suspension between the inward and the outward flow is critically important. We notice a similar pattern in our breathing: there is an inhalation and an exhalation, and between them a liminal moment of suspension. (To offer a contrast, a metronome or a pendulum also exhibits a steady alternation, but without impetus or recovery.)

Swings can be done in all sorts of configurations using the torso, legs, and arms in many directions and degrees of complexity. The breath is consciously free; sound adds depth to the movement. The Swings are about release and can be very pleasurable. At the same time they require great specificity: parts of the body are still and controlled; other parts are moving in an open way. The body becomes a dynamic physical “text,” connecting an actor’s breath, impulse, and physical expression.

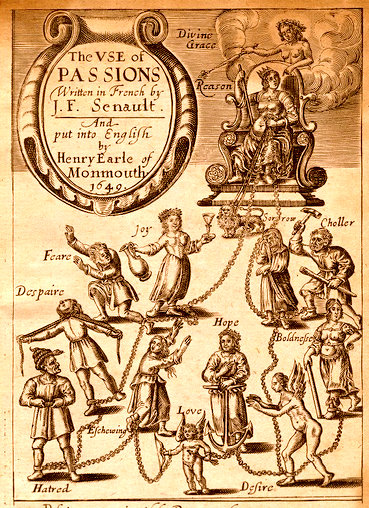

Once the actor’s instrument becomes more upright, flexible, strong, and available, the goal is to increase the ability to express through a range of forms and characters what it means to be human. The athletic Cat sequence, the dimensions, animal studies, elements, animals, seven deadly sins, period dance and mask work – all of these exercises strengthen the connections between impulse, release, and expression.

Arnold’s swing work originated from her studies with Sigurd Leeder, the pedagogue of the Jooss Ballet. Kurt Jooss and Leeder were former students of Rudolf Laban, and they advanced his work even as they created their own expression in modern dance. Arnold then re-imagined and shaped this work for specific application to actors, in an exchange with her exceptional colleagues at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Arts (LAMDA): the head and acting teacher, Michael McOwen; Iris Warren, the powerful voice teacher; and Norman Ayrton, who taught movement and mask. McOwen and Ayrton were trained by Michel St. Denis, who had brought to England the work of the French master of the early 1900s, Jacques Copeau. Trish fleshed out this French strand by taking a workshop in the 1970’s with Jacques Lecoq, who had developed his powerful work from the legacy of Copeau.

Thus both German and French influences informed Arnold’s practice of actor training, which she developed during her many years at LAMDA. She later came to NYU and The Working Theater in New York with Kristin Linklater, complementing Linklater’s voice work, and finished her distinguished teaching career at The Guildhall School in London.

In 2008 I made a 2 DVD-set documentary to honor Trish and her work, called Tea with Trish. It is both handbook and commentary, annotating the progression of the movement work, along with discussion and analysis by Trish and several movement practitioners about the exercises, the history, and its transmission to future generations.

Mindbody Perception & Physical Awareness

There is something about an actor which is dependent on what he is in himself, that certifies his authenticity, makes a tonal impression on us; knowing, from the moment he steps on stage, from his simple presence, even before he has spoken a word, that there is no possibility of deception. – Jacques Copeau, Texts on Theatre (1929)

Our current culture emphasizes surface and speed. These values, while promoting certain attributes, do not encourage actors to develop their interiority or to make connections between interior and exterior, which are vital for their work. In my current teaching I focus on building interior pathways, which help actors to look and listen more deliberately to the mindbody.

The painter Pierre Bonnard talked about “the demands and the pleasures of seeing and its rewards: crude seeing and intelligent seeing.” Crude seeing addresses the cursory identification of what’s in front of a person. This skill has been refined by electronic advances and the amount of information to which we are now constantly exposed. Intelligent seeing, on the other hand, joins looking and perceiving: through the senses we distinguish and interpret. For the actor, “intelligent seeing” can be developed through work with physical awareness. It is both an inward – and an outward – looking journey, in which the senses and sensations become more attuned and precise, and the natural loops of imagining and remembering, feeling and understanding are reinscribed in the mindbody.

Too often we forget the natural context in which we live, and imagine ourselves as isolated beings. Increasing our awareness of the body’s location in space – inside/outside, front/back, down/up – brings us into relationship with the world in which we find ourselves, the people around us, the space we are in, and gives us shape for the past and future. As Willa Cather wrote, “Miracles rest not so much upon faces or voices or healing power coming to us from afar off, but on our perceptions being made finer, so that for a moment our eyes can see and our ears can hear what is there about us always.” Actors must foster that healing power and bring it to the stage, in order to move their audiences to perceive more finely the miracles of “what is there about us always.”

The actor needs to practice connecting more deeply with the world around her, and aligning it to inner landscapes of imagination, image, and memory. This will allow her to imagine herself more easily into other human shapes and situations. “In the act of perception,” David Abram writes in The Spell of the Sensuous,

I enter into a sympathetic relation with the perceived, which is possible only because neither my body nor the sensible exists outside the flux of time, and so each has its own dynamism, its own pulsation and style. Perception, in this sense, is an attunement or synchronization between my own rhythms and the rhythms of the things themselves, their own tones and textures.

The study lasts a lifetime. For actors, it builds sensorial and perceptual thinking, and increases the ease of traveling inwardly and outwardly following the path of the breath: information from the outside world traveling in with every inhalation, and the inside world released with every exhalation.

“The cosmos can be regarded as a vast human body,” wrote Victor Turner. The reverse also applies: the human body may be regarded as a cosmos. Enlarging the worlds inside and outside and strengthening the pathways between them creates a flow of life large enough for the theatre.

Movement into Character

Our own bodily position, attitude, condition, is one of the things of which some awareness, however inattentive, invariably accompanies the knowledge of whatever else we know. – William James, The Principles of Psychology (1890)

Physical inhabitation of character – through gesture, posture, weight and heft, initiation to movement, physical relationship to others and to the space itself -communicates immediately and deeply to the audience; the spoken text is carried along by that information. If, as Mark Johnson says, “every thought implicates a certain bodily awareness,” then actors must fully inhabit the precision of each thought.

I am fascinated by how much is taken in by the audience – powerful clues about character, personality, class, gender, age, location. In the simplest of terms, we recognize a king on stage not only by his crown and his bearing, but also by how others relate to him – how they approach, how close they get to him, and much more.

I am fascinated by how much is taken in by the audience – powerful clues about character, personality, class, gender, age, location. In the simplest of terms, we recognize a king on stage not only by his crown and his bearing, but also by how others relate to him – how they approach, how close they get to him, and much more.

All relationships imply a negotiation of status, or what Keith Johnstone calls status transactions in his classic book, Impro. I work with actors on developing both a strong physical awareness and a language for inhabiting status: how we ourselves habitually “perform,” and how we can adopt other strategies to add to our range.

There are several layers of this work – hierarchical realities within the world of the play that don’t change, and relationship shifts within the scenes. Actors need to flesh out the delicate adjustments that characters make, reflecting the unconscious complexity people enact in the outside world.

The English director Max Stafford-Clark provides an example of exploring status work in a profound way. In Letters to George he traces his direction of a Restoration play, The Recruiting Officer, at the Royal Court in London in the 1980s. (The book is written in the form of imaginary letters to the author George Farquer.) Stafford-Clark describes the challenge posed by that classic marker of status, the bow:

The manner in which characters greet each other is enormously revealing. I’m not convinced that our social observation in this department has been very detailed… The trouble is that our only cultural reference point is other productions of Restoration plays.

Stafford-Clark knew that just mimicking a period bow would not communicate the full range of implications embedded in that physical “text”. Instead, he embarked on an inquiry into status relationships during the Restoration period, combing accounts that included descriptions of manners, customs and exchanges between people, and creating a series of exercises. Actors first greeted one another “as themselves” in the present; then they improvised scenes with different configurations of gender, age, relationship, etc. The company began to discern a “network of…signals,” which, when they returned to the text, allowed them to see and bring expression to a range of nuance they had not perceived before. They were able to extrapolate social, physical, and political clues to enactments of power in society, making their production all that more complex, embodied, and relevant to a contemporary audience.

Stafford-Clark knew that just mimicking a period bow would not communicate the full range of implications embedded in that physical “text”. Instead, he embarked on an inquiry into status relationships during the Restoration period, combing accounts that included descriptions of manners, customs and exchanges between people, and creating a series of exercises. Actors first greeted one another “as themselves” in the present; then they improvised scenes with different configurations of gender, age, relationship, etc. The company began to discern a “network of…signals,” which, when they returned to the text, allowed them to see and bring expression to a range of nuance they had not perceived before. They were able to extrapolate social, physical, and political clues to enactments of power in society, making their production all that more complex, embodied, and relevant to a contemporary audience.

Such commitment to exploring the depth of status interplay is rare: directors often don’t have the time. A knowledgeable movement director is usually the one to address it when there are sufficient resources in a production. But all actors benefit from developing their own skills in the physical expression of the spoken and unspoken text as part of what they bring to their work, whether in the context of representing status or in the limitless other contexts in which physicality denotes meaning.

The goal is to create the full expression of people relating to one another and to their environments. In her Pictorial Autobiography (1985), the English sculptor Barbara Hepworth describes something she observed in a public square that captures for me what we aspire to achieve.

My first visit to Venice; and against the superb proportions of the buildings I watched new movements of people…. As soon as people, or groups of people, entered the Piazza they responded to the proportions of the architectural space. They walked differently, discovering their innate dignity. They grouped themselves in unconscious recognition of their importance in relation to each other as human beings…. I noticed in Venice generally that there were particular movements of happiness springing from a mood among people which seemed to imbue them at once with greater swiftness and certainty of movement and gesture, and at the same time a greater relaxation.

Actors can exert a profound effect on the audience if, fully conscious and in control of articulating their physical expression, they experience an embodied reality up there on stage.

Actor-Audience Explorations

Performing Clown, I have enjoyed an open relationship with the audience, in which every action on stage is fed by an interaction with the public. This openness is not appropriate to every kind of theatre: imagine gazing out to the audience with each beat of A Streetcar Named Desire! Different forms of theatre imply different relationships between actor and audience: the closed “fourth wall” of naturalism; the solicitation of the upper balcony for the melodramatic actor; the direct address to the audience in a Shakespearean aside, in contrast to the rest of the play; the welcoming inclusion of the audience in a drawing-room drama of Oscar Wilde. How overtly does the actor acknowledge being on stage in front of an audience? Each form of theatre requires an understanding of the correct and conscious rapport between the player and the public.

Creating Emotion from Sensation

Before there is abstract thinking, before there is reasoning, before there is speech, there is emotion. – Mark Johnson, The Meaning of the Body (2005)

Behavior is rarely rational; it is habitually emotional. We may speak words wisely as the result of reasoning, but the entire being reacts to feeling. For every thought supported by feeling, there is a muscle change. Primary muscle patterns being the biological heritage of man, man’s whole body records his emotional thinking. – Mabel Todd, The Thinking Body (1937)

I keep returning to the indivisibility of the body and mind, the physicality of emotion and thought. Charles Darwin and William James wrote about the importance of emotions for the human organism’s understanding of the world: this knowledge is used widely now in advertising and charity fundraising appeals. Brain researchers John Allman, Antonio Damasio, and others have suggested that we dispense with the idea that emotions and rational thought are separate: both are visceral responses – and help us make sense of our surroundings. Applying all this to the theater, the audience watches the actor intently, interpreting each gesture and nuance of the performance onstage in order to understand what is happening; that understanding arises from the physical sensation of empathy.

In American theatre schools, the usual practice is to train actors to access emotion through the memory of a past experience, or through imagining an experience comparable to the situation of the character. But what if, as actors, we can’t imagine, or haven’t lived through a comparable experience? What if a memory is too traumatic to draw upon with ease? And how can we summon it fully, on demand, time after time?

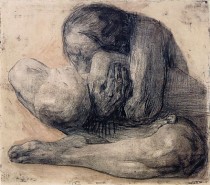

The ability to convey emotional truth is a vital tool for actors. The audience’s empathetic link can only be made to something they feel from onstage: for years I have been working on a solution to the demand for specific and authentic emotional expression, which is to gain access to emotion through sensation. Recent studies on the brain have shown that emotion does not start with thought at all, but begins in the body, which sends signals to the brain alerting the brain to change. A series of actions then ensue to make humans able to realize they are experiencing an emotion. With this research in mind I have developed a series of exercises that from a purely physical foundation can elicit basic emotions: a prescribed breath pattern, empathetic mimicry, and elicited physical sensations can actually trigger the emotions of joy, sorrow, fear, and rage.

In the Emotion from Sensation work, we become comfortable gaining access to the basic flow of primary emotions, and then advance to examine each emotion’s range of expression, from the most delicate to the most potent, from the twitch of irritation to rage. This summons up Laurent Joubert’s spectrum of laughter (gamme de rire) from the smallest titter to the largest guffaw. With these skills, actors increase their confidence that they will be able to find within themselves the strong emotions required, to “come up with the goods” for each performance – and to use that emotional stream with greater precision and nuance.

© Merry Conway, 2011. All rights reserved